Spanish Old Master Drawings

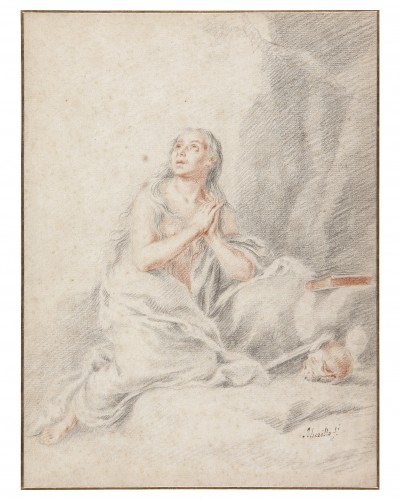

The penitent Magdalen

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

(Seville, 1617-Cadiz, 1682)

- Date: c. 1665

- Black and red chalk on paper

- 280 x 210 mm

- Signed: “Murillo fe” at the lower right corner

- Provenance: Library of Seville Cathedral; acquired around 1790 by the Baron St. Helens in Seville; London, 1840, sale of the St. Helens collection (lot 115), acquired by William Buchanan; John Rushout, 2nd Earl of Northwick; Sir William Stirling Maxwell; Sotheby’s, Stirling sale, 21 October 1964 (lot 24); Christie’s, 11 March 1975 (lot 132); Christie’s 30 September 1975 (lot 115); Madrid, private collection (1976).

- SOLD TO A PRIVATE COLLECTOR

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo was born in Seville in 1617. His parents died when he was nine and he was brought up by his elder brother and his brother-in-law, who was a surgeon like his father. Little is known of Murillo’s early studies, but according to Palomino he trained in the studio of the painter Juan del Castillo (c.1590-1657). Murillo’s first major project dates from 1645-1646 when he was commissioned to execute a series of paintings for the cloister of the monastery of San Francisco in Seville. The success that he enjoyed brought him numerous commissions from the Church in Seville. In 1660, following a brief trip to Madrid, Murillo co-founded with Francisco Herrera el Mozo the Academy of Painting in Seville with the aim of improving the teaching of painters, particularly young students.

read more

In 1663 Murillo’s wife died and two years later he became a member of the Hermandad de la Caridad [Confraternity of Charity], for whom he would execute some of his most important works. The last two decades of his life saw the consolidation of Murillo’s fame and prestige within the art world in Andalucía. His work, which had been enriched by what he had seen in Madrid and by the presence of numerous Flemish and Dutch paintings in Sevillian churches and palaces, would attain ever greater levels of technical quality and aesthetic sensibility. As a result Murillo was known and admired not only in Spain but also abroad, and he was the only Spanish artist of the day known in Europe, primarily for his genre scenes. Murillo died in 1682 as a result of the injuries that he sustained falling from the scaffolding when painting the main altarpieces for the Capuchin monastery in Cadiz.

The present drawing is a preparatory study for The penitent Magdalen in the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in Cologne (139.5 x 188.5 cm).1 It was one of a group of seven paintings owned by the Genoese merchant Giovanni Bielato, who lived in Cadiz until his death in 1674. In his will Bielato donated his paintings to the Capuchin church in Genoa, stating “avere in casa sua, nel salotto a pian di sala, sette quadri di mano e penello di Bartolomeo Moriglio di Siviglia; coiè uno grande della Santissima Natività di N. Signore, altro simile della Historia di Giuseppe, due dell’istezza altezza, ma più stretti, uno cioè con N. Signora che va in Egitto et altro di S. Tomaso de Villanova, due altri, poco più basi e più stretti, in uno dei quali è l’immagine di N. Signora dell’Imacolata Concettione e l’altro di S. Maria Maddalenae il settimo piccolo di S. Gio. Battista; tutti questi setti quadri, che sono, como si è detto, della mano del Moriglio, li lascia alli R. Padri Cappuccini della SS. Concettione di Genova, perchè li ponghino nel loro choro.” 2 The paintings remained in situ until the early 19th century, when they were acquired between 1803 and 1806 by Mr. Irvine for various English collectors, as noted by Buchanan in his Memoirs of Paintings. 3 In the present day the group is divided between various museums and private collections: Joseph thrown into the Well, The Adoration of the Shepherds and Saint Thomas of Villanueva distributing Alms are in the Wallace Collection in London; The Immaculate Conception is in the Nelson Atkins Gallery of Art, Kansas; The Rest on the Flight into Egypt is in the collection of the Earl of Strafford; and The young Saint John the Baptist is in the collection of Mrs. Alfred G. Wilson in Rochester (Michigan). With regard to The penitent Magdalen, in 1824 Buchanan noted that it “was for some time in the possession of Mr. Walsh Porter”, 4 subsequently passing through various hands until it entered the Wallraf-Richartz Museum in 1936.

As with the canvas now in Cologne, the history of the present drawing can be followed in detail up to the present day. The first reference to it dates from 1840 when it was offered in the sale of the drawings of Alleyne Fitzherbert, Baron St. Helens, sold at Christie & Mason in London. 5 The Baron, who had been English ambassador to Spain in the 1790s, had assembled a group of more than seventy drawings by Murillo. In the sale catalogue, dated 26 May 1840, it is stated that they had been acquired by him from the library of Seville Cathedral during his stay in that city: “obtained from the Cathedral Library, at Seville.” The present drawing is included in the section of drawings executed in red and black chalk and is described as “115. The Magdalene praying”, while the buyer is noted as William Buchanan. The drawing subsequently passed into the ownership of John Rushout, 2nd Earl of Northwick, before being owned by Sir William Stirling Maxwell, the great 19th-century expert on Spanish paintings, particularly Velázquez and Murillo. 6 It was offered at the Stirling sale at Sotheby’s on 21 October 1964 (lot 24) and was subsequently sold at Christie’s on 30 September 1975 (lot 115), 7 when it was acquired by a Madrid collector. Jonathan Brown lists it in that collection in his study of Murillo’s drawings of 1976 (cat. no. 31).

The painting and drawing can be compared. The painting depicts the penitent Magdalen as a young woman praying in the desert. She is kneeling, her hands joined and her face turned to the right to look at three small, musical angels descending from heaven. On the right of the composition are the Magdalen’s typical attributes of a book, cross and skull, all referring to the hermit’s life, as well as a flask of perfume. These elements are set in a fine landscape of ochre tones that looks back to Titian’s depiction of Mary Magdalen of the previous century. 8 The present drawing contains all the elements of the painting in detail with one exception in that the composition is slightly reduced and thus offers a more concentrated focus on the Magdalen, who is located almost in the immediate foreground. The landscape is very lightly sketched in and lacks the musical angels in the upper left corner.

The present drawing has been described by experts including Jonathan Brown as one of the finest by Murillo.9 It is executed in black and red chalk, a technique that allowed the artist to particularly define certain elements of the composition. The red chalk, for example, is used to define the parts of the Magdalen’s body and certain details such as the pages of the book resting on the rock and the skull with the crucifixion leaning against it. Using this red chalk and applying it with more or less pressure to obtain darker or lighter tones, the artist emphasised the volumes of the body and created gradations in the lighter areas and the shadows. Murillo worked with black chalk in the same manner; in order to highlight the Magdalen’s hair he pressed harder to create these lines, while the outlines of the clothing and landscape are created with light strokes applied in a diagonal direction.

As in the case of Ribera and Alonso Cano, numerous drawings are known by Murillo, a fact that distinguishes these artists from their Spanish contemporaries. The varied nature of Murillo’s drawings allows us to become familiar with the different techniques that he employed. 10 Some use a mixed technique that combines black and red chalk, on occasions with highlights in white lead or white chalk. This technique first appeared in Italy in the 16th century and arrived in Spain in the following century, and Murillo was among the artists who most effectively used it. 11 As Jonathan Brown has noted, the most conclusive proof of the existence of this type of drawing within Murillo’s oeuvre is the group that was owned by the Baron St Helens, to which the present sheet belonged. 12 They are highly finished drawings in which the artist focused his attention on the principal figures in the compositions, subsequently translating them onto the canvas where they were located in broader spatial settings. Examples include The Immaculate Conception in the Statens Museum for Kunst in Copenhagen or the Saint Francis of Paola in the British Museum, London (inv. 1850-07-13-2), the latter conceived in a way very similar to the present Magdalen.

Finally, it is worth making brief reference to the other techniques deployed by Murillo in his drawings. Most are executed in pen and wash. As Pérez Sánchez noted: “the stroke of the pen is agitated and broken and the yellow wash becomes thicker or lighter, giving a vibrant sensation of volume and movement.” 13 Examples of this type include The Annunciation in the Museo del Prado (D-5998), and the Saint Isidro in the Louvre (inv. 18445). In some sheets the artist also applied black or red chalk in very light strokes that sketch out some of the principal elements in the composition, which he then went over with a pen or brush. In addition, some drawings use black chalk, as in the series of Angels with the Instruments of the Passion in the Louvre (inv. 18430-38) or the Saint Diego de Alcalá in the Hamburg Kunsthalle (c. 1645, inv. 385991). Finally, some drawings use both black and red chalk, of which the best known example is The Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, again in the Hamburg Kunsthalle (inv. 38592).

[1] Angulo, Diego, Murillo. Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1981, vol. II, pp.280-281, cat. no. 356; and Ureña Uceda, Alfredo, “La pintura andaluza en el coleccionismos de los siglos XVII y XVIII” in Cuadernos de Arte e Iconografía, vol. VII, no. 13, Madrid, Fundación Universitaria Española, 1988, p.134.

[2] Angulo, Diego, Murillo. Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1981, vol. II, pp.102-103.

[3] Buchanan, William, Memoirs of Painting, with a chronological history of the importation of pictures by the Great Masters into England since the French revolution. London, Printed for Ackermann, 1824, vol. II, pp. 144 and 172. See also Stirling Maxwell, William, Annals of the artists of Spain. London, J. Olivier, 1848, vol. II, p.877.

[4] Buchanan, William, Memoirs of Painting, with a chronological history of the importation of pictures by the Great Masters into England since the French revolution. London, Printed for Ackermann, 1824, vol. II, p.172, no. 5.

[5] See A Catalogue of the Valuable and Choice Collection of Drawings by the Ancient Masters of the Italian, French and Dutch Schools; a highly interesting assemblage of sketches by Murillo obtained from the Cathedral Library, at Seville, and few prints. The property of the late Right Hon. Lord St. Helens. Christie & Mason, Tuesday, May 26th, 1840, lot 115; Brown, Jonathan, Murillo and his Drawings. The Art Museum, Princeton University, 1976, p.108, cat. no. 31 and pp.191-192; and Mena Marqués, Manuela, “Murillo dibujante” in Murillo (1617-1682). Exhibition catalogue, Madrid, Museo del Prado, and London, Royal Academy of Arts, 1982, p.78.

[6] For Murillo, see Stirling Maxwell, William, Annals of the artists of Spain. London, J. Olivier, 1848, vol. II, pp.825-928.

[7] Angulo refers to the appearance of the drawing in this auction. See Angulo, Diego, Murillo. Madrid, Espasa Calpe, 1981, vol. II, p.280.

[8] The success of Titian’s compositions, particularly his depictions of Mary Magdalen, were such that these works soon became models imitated by other artists. As a result of their widespread dissemination, partly due to the large number of prints after them, that they became prototypes used by painters for their own compositions. Within the oeuvre of Murillo, examples include the present work, in addition to the depictions of the Magdalen by Alonso Cano, and in particular, by Mateo Cerezo.

[9] Brown, Jonathan, Murillo and his Drawings. The Art Museum, Princeton University, 1976, p.108, cat. no. 31.

[10] On Murillo’s drawings see Brown, Jonathan, Murillo and his Drawings. The Art Museum, Princeton University, 1976; Angulo, Diego, “Recesión: Exposición de dibujos de Murillo en Princeton” in Archivo Español de Arte. Madrid, 1977, pp. 337ff; Hyatt Major, A., “Recesion: J. Brown, Murillo and his Drawings” in Master Drawings, no. 2, 1977, pp.184-185; Mena Marqués, Manuela, “Murillo dibujante” in Murillo (1617-1682). Exhibition catalogue, Madrid, Museo del Prado, and London, Royal Academy of Arts, 1982, pp.77-90; Dibujo Español de los Siglos de Oro. Exhibition catalogue, Madrid, Dirección General del Patrimonio Artístico, Archivos y Museos, 1980, pp.22-23 and 87-182; and more recently, Boubli, Lizzie, Inventaire général des dessins. École espagnole XVIe-XVIIIe siécle. Paris, Musée du Louvre, 2002, pp.95-112.

[11] See Mena Marqués, Manuela, “Murillo dibujante” in Murillo (1617-1682). Exhibition catalogue, Madrid, Museo del Prado, and London, Royal Academy of Arts, 1982, p.85.

[12] Brown, Jonathan, Murillo and his Drawings. The Art Museum, Princeton University, 1976, pp.28-29.

[13] See the essay by Pérez Sánchez in Dibujo Español de los Siglos de Oro. Exhibition catalogue, Madrid, Dirección General del Patrimonio Artístico, Archivos y Museos, 1980, p.23.