Spanish Old Master Drawings

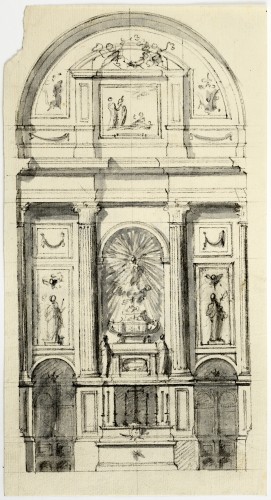

Initial sketch for the principal altar of the Colegiata de San Isidro

Ventura Rodríguez

(Ciempozuelos, Madrid, 1717-Madrid, 1785)

- Date: 1768

- Black chalk and grey wash on laid paper

- 291 x 157 mm

- Inscribed: “Carpeta XIX/ Nº 2.926”, in pencil, on the reverse

- Provenance: Madrid, collection of the Marquis of Casa-Torres; Madrid, private collection

In 1567 the Company of Jesus inaugurated a small chapel dedicated to Saint Peter and Saint Paul on calle Toledo, to which a seminary would subsequently be attached. In 1622 the chapel was demolished in order to build a new church, in accordance with the instructions of the Empress Maria of Austria, daughter of Charles I, who bequeathed her fortune to the Jesuits with the aim of constructing the new building. It was designed by the architect Pedro Sánchez although construction was subsequently supervised by Francisco Bautista and Melchor de Bueras. On 23 September 1651 the church was consecrated and dedicated to Saint Francis Xavier. At the moment of its consecration the church was not yet finished but it seems that the principal altarpiece was installed, comprising three storeys crowned at the top with a large painting commissioned in Antwerp from Cornelis Schut the Elder and depicting Saint Francis Xavier baptising the indigenous South Americans, painted in 1648. 1

read more

In 1767 the Jesuits were expelled from Spain due to their excessive political and financial power. On 2 April of that year Charles III signed the Prágmatica Sanción drawn up by Pedro Rodríguez de Campomanes, lawyer of the Council of Castile. 2 This document authorised the suppression of the religious Order in all territories of the Spanish Crown and decreed the seizure of their possessions. A year later, in 1768, Charles III decided to transform the Colegio Imperial, dedicated to Saint Francis Xavier and the principal religious house of the Jesuits in Madrid, into a church dedicated to Saint Isidore the Labourer, the city’s patron saint. For this reason, in 1769 Isidore’s remains, which rested in the chapel of San Andrés in Madrid, were transferred together with those of his wife Saint Mary of the Head, in order to be venerated in the new church. 3 A series of alterations were also undertaken to transform the church into a collegiate one with a new dedication.

As architect to the Council of Castile and one of the most prestigious in Spain, Ventura Rodríguez was commissioned to undertake this remodelling, described by Antonio Ponz just five years after work was completed: “[In the presbytery] in place of the old and capricious architectural order, [Ventura Rodríguez] designed Corinthian pilasters and an entablature; he adorned the vault with excellent taste; he installed the organs, also of Corinthian design, in two tribunes; he installed the altar table in the middle and around it designed the chaplains’ choir. He retained the old altarpiece, of which the first level had four composite columns, gilding the elements that ought to be gilded and painting the rest to imitate different marbles; and in a large niche in the centre he placed the urns of the two saints, on a throne of clouds a statue of Saint Isidore by Juan Pascual de Mena, and to either side two allegorical statues, one by Francisco Gutiérrez and the other by Manuel Álvarez. As a complement to all this, on the second level he installed a large painting by Anton Raphael Mengs, representing a glory with the Holy Trinity… Between the pilasters of the pillars and looking towards the presbytery he installed various statues of labourer saints in the niches, sculpted by the above-mentioned Pereira, which were formerly in the old chapel of Saint Isidore.” 4

Four drawings by Ventura Rodríguez are known for this project: two ground-plans of the church and some of its adjoining buildings; a ground-plan and elevation for the remodelling of the presbytery; and an elevation of the organ. 5 However, until now no drawing was known relating to the remodelling of the principal altar, one of the most important elements of Ventura Rodríguez’s project for the redesign of the presbytery. The present sheet is an initial sketch for its redesign, respecting the previous architectural masses and different elements but completely rethinking the decoration. The drawing depicts an altarpiece divided into three horizontal and three vertical sections separated by four composite columns, as the previous altarpiece had, according to Ponz. The bottom storey shows the new form of the altar, which now projects forward into the presbytery in order to allow for the installation of choirstalls for fifty-six chaplains, as required by the liturgy in the case of a royal collegiate church. The two lower arches that enclose a series of double arcades are thus the initial idea for the installation of the choirstalls to either side of the altar, their appearance and arrangement over two levels conforming to the elevation of this element in the drawing for the Presbytery in the Archivo Histórico Nacional (fig. 1, AHN, Consejos Suprimidos, MPD 691). In this initial sketch by Ventura Rodríguez it would seem that the choirstalls did not completely surround the altar but rather that two double stalls were adapted at the base of the lateral sections of the altarpiece. Nor was the back part completely covered by stalls, as was finally the case, as Ponz described. In addition, two later visual sources show what was finally executed prior to the fire that destroyed the altarpiece in 1936. These confirm that the structure of the choirstalls completely surrounded the presbytery, leaving the altarpiece set back. This can be seen in the painting by Joaquín Sigüenza y Chavarrieta of around 1857-58, The Meeting of the Chapter of the Military Orders for the Investiture of Alfonso XII as Grand Master (fig. 2, Madrid, Senado), and in another by Joaquín Muñoz Morillejo, High Mass in the Cathedral of Madrid, of 1921 (fig. 3, Madrid, Museo de San Isidro, inv. no. 1496).

In the drawing, the second storey of the altarpiece is divided by four striated composite columns. The central, much wider section had a large niche with a round-arched top which housed the urns of Saint Mary of the Head and Saint Isidore the Labourer, one above the other. The latter was crowned with a sculptural group representing The Glorification of Saint Isidore set on a large throne of clouds from which a multitude of luminous beams emerge. Two sculptures accompanied this work. The contents of the present sketch perfectly correspond to what was finally carried out (see figs. 2 and 3), with the group by Juan Pascual de Mena presiding over the altarpiece and framed at the sides by the figures of Faith, executed by Manuel Álvarez, and Humility, by Francisco Gutiérrez. In this initial sketch the lateral sections of the altar, which were narrower, include a large rectangular niche that housed the figure of a saint crowned by a small angel. Above this was a rectangular compartment framing a decorative garland. The final arrangement of the lateral sections varied considerably with regard to the sketch; as can be seen in the above-mentioned 19th– and 20th-century paintings that show the interior of the collegiate church of San Isidro (figs. 2 and 3), this arrangement was replaced by the installation of two niches with rounded tops housing labourer saints: on the left, from top to bottom, Saints Alexander and Eustace; and on the right, Saints Elisha and Orentius. These four sculptures were executed by Manuel Pereira for the chapel of San Isidro around 1657 and were moved to the Colegiata and painted white to adapt to them to Neo-classical taste and to their new location. Above them, at the height of the capitals of the columns, an architectural frame with an inset garland was retained but was much smaller in scale than the one initially present.

The top storey of the altarpiece occupied the semicircle below the barrel vault which spanned the presbytery. This rested on an entablature and a frieze that is shown without decoration in the drawing and which appears in the above-mentioned, later paintings with interlaced garlands that are gilded to produce an elaborate effect. In the sketch the central section of the top storey still seems to refer to Cornelis Schut’s large-scale painting of Saint Francis Xavier baptising the indigenous South Americans, of which the composition is known from a preparatory oil sketch in the Jesuit church in Bruges (fig. 4), 6 and in which the three principal figures seem to be the ones in Ventura Rodríguez’s drawing. An arch-topped frontal completed the central vertical section which housed two small angels bearing a laurel wreath, crowning the entire work and executed in stucco. In the lateral sections two coats-of-arms are lightly suggested. The sketchy presence of Schut’s painting locates the execution of this first idea for the remodelling of the altarpiece’s decoration to a date later than January 1769 on the basis of a letter of that date which refers to the substitution of that painting with The Holy Trinity by Anton Raphael Mengs: “In the second storey of the altar is a painting measuring 23 feet high by 13.5 wide [approx. 644 x 378 cm] depicting S. Francis Xavier baptising Jews; a rather commonplace painting and out of date […] and I considered it appropriate that don Antonio Mengs should see it, and in accordance with this don Ventura Rodríguez stated that it would not serve as it was in such bad condition as well as being inappropriate and not in harmony with the others in the altarpiece or with their meaning. For this reason it has been necessary to commission Mengs to paint another of the Throne of the Holy Trinity, with the Immaculate Conception below it on the right and on the other side Saint James, Saint Lawrence and Saint Damasus positioned as if receiving the Holy Throne as it ascends to heaven; and I consider it most appropriate. The painting is typical of the artist and I hope that it receives general approbation and attracts attention from the public for its magnificence and gravity.” 7 Mengs painted his large-scale work rapidly, completing it in forty days, which suggests that he had studio assistance. 8 He charged a fee of 60,000 reales which was paid to him by the Count of Campomanes, one of the key figures in the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain. 9

The present sheet is thus an initial sketch for the decorative remodelling that Ventura Rodríguez intended to undertake on the Jesuit altarpiece in order to make it the principal axis of the Colegiata in honour of Saint Isidore. As observed above, this drawing includes a series of elements that would appear in the final design, including the central zone with the urns and the sculpture of The Glorification of Saint Isidore by Juan Pascual de Mena. It also includes elements that the architect was still considering, such as the placement of the choirstalls, the arrangement of the sculptures in the lateral sections of the altarpiece and the canvas at the top. The preliminary nature of this design explains why it was not executed in Indian ink and rather entirely in a soft chalk that allowed the figures to be more easily suggested, with some light grey washes added to emphasise the shadows. Here the only element that really interested Ventura Rodríguez was the structure of the altarpiece (defined with a finer and harder chalk), which undoubtedly reflected the disposition of masses of the Jesuits’ original altarpiece, while the figures and ornamental elements are rapidly indicated, revealing Ventura’s primary concern as a good architect to convey the structure from the outset. Furthermore, for a project of this type, in which the altarpiece was already executed and was merely being remodelled with regard to its decoration, there was no need for heights and measurements, which are thus absent from the drawing.

A drawing comparable to the present one is the design for the Altarpiece in the Chapel of Our Lady of Bethlehem in the Church of San Sebastián, in which the architecture is also much more defined than the figures and ornamentation (fig. 5, Museo Nacional del Prado). 10 In addition, in both cases the fact that these are initial designs means that the ornamental elements are only very schematically rendered while the two works do not have the date and signature that the artist usually applied in the case of finished projects. Finally, the fact that the drawing is by an architect is also indicated by the presence of a small sketch of an architectural structure on the reverse. Thus, both drawing of the architecture and the sculpture and the known involvement of Ventura Rodríguez in this project means that the present sheet can be securely attributed to that Madrid architect.

- On this now lost canvas, see Gálvez (1926), pp. 670-674 and 736-737; Gutiérrez Pastor (2007), pp. 105-106, 112, 114, 116 and Sanzsalazar (2013), p. 203.

- On the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain, see Pinedo (1996).

- Ventura Rodríguez (2018), p. 299.

- Ponz (1772-1794/1947), pp. 435-436.

- Only two of these drawings are signed by the architect; however, the other two are also considered to be by his hand due to his direct involvement in the work to remodel the church into a collegiate one. Ventura Rodríguez (2018), pp. 299-304.

- Gutiérrez Pastor (2007), pp. 115-116, fig. 15, and Begheyn (2006).

- Letter from Pedro de Ávila y Soto to Manuel de Roda. See González Arribas & Arribas Arranz (1961), pp. 176-177 and Roettgen (1999), vol. I, p. 492, cat. QU48.

- Roettgen (2010), p. 235. Mengs is known to have had a large studio which assisted him in the creation of the majority of his works. The painting was destroyed by fire in 1936 during the Civil War but a preliminary oil sketch survives. In addition, the above-mentioned visual sources show its composition. See Fecit II (2010), pp. 37-41, cat. 8.

- Carrete Parrondo (1978), p. 171.

- Ventura Rodríguez (2018), pp. 526-527, cat. 132.